The first thing I noticed when I started working in PR (oh God, 10 years ago) was that most people seemed to be slightly frazzled. Even when it looked like they had nothing much going on. There was a perpetual sense of “this cannot last, something massive, annoying and complex is going to drop on my lap at 5:30, I just know it”.

I was used to working in a support role, and support staff know that time is never their own. It belongs to the team, or the executive, that they support. But as my role in Carrot evolved from a support function to copywriting I realised that my attitude to my time hadn’t made the transition.

I still prioritised other people’s actions. I took on responsibilities and tasks without thinking about how I’d fit them into the day or week, because I could always fit something else in. So what if it left me with no time to think?

Not robots

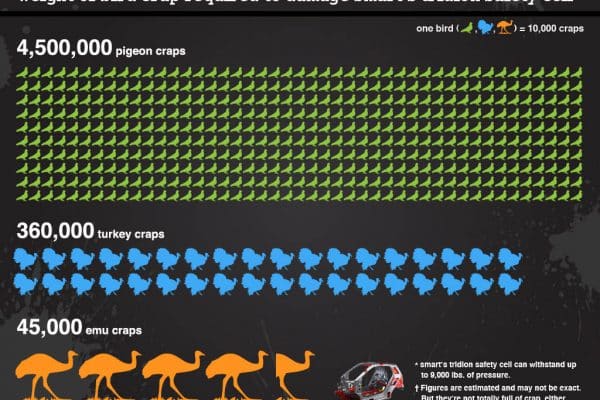

The thing is people aren’t machines. We need to gather around watercoolers (real or virtual) and have a natter. We need to take walks in the park. We need to open that bizarre video of singing Australian children’s TV presenters that our colleague insisted we watch (you know who you are!).

Work – or even just think about work – from dawn until dusk and in the long-run you achieve nothing but burnout.

Setting expectations

Before Christmas, the Carrot team took part in a brilliant training session run by Rachel Boothroyd. The training made us realise that productivity isn’t about traditional time management. To be truly productive, to create, we need to manage our ability to focus. We need to listen to, and look after, our prefrontal cortex (PFC).

David Kadavy does a great job of breaking down the role of the prefrontal cortex in task management and completion, but to sum up, it appears to be the proactive, thinking, analysing part of the brain. The amygdala is the reactive part, always on alert, constantly distracted by email, IM and cat videos.

The PFC responds well to focused work, but has difficulty when we continually switch between tasks – which is what we’re doing when we think we’re multitasking. While we may think we’re being ultra productive by keeping an eye on our email and social media accounts while also writing an article, what we’re actually doing is draining our PFC’s energy reserves. The more we are interrupted (or we distract ourselves) the harder it is to get back on track. By the end of the day our capacity to create, focus and think is severely limited.

We don’t need to be ‘always on’

I’d fallen into the habit of always being available. It feels rude to set myself to ‘do not disturb’ on Skype. What if someone needs something, right now? (Yeah …unless you’re running the country and someone has just pressed a big red button, chances are whoever is Skyping you can wait a few minutes.)

If I want to focus on writing and being creative, I need to look after my prefrontal cortex. This means:

- Planning to accomplish three main tasks a day.

- Using group accountability to track productivity (a quick 2-minute chat with the rest of the team to see if we’ve managed to hit our goals during the previous day and to share our tasks for the day ahead).

- Rewarding productive work. Using something like the Pomodoro technique not only lets you break tasks down into manageable chunks, but it gives you a few minutes rest between work sessions to sort of reset your brain (maybe by practicing some mindfulness exercises or simply by going outside for some fresh air).

PR is an industry notorious for having an ‘always on’ culture. We need to know what’s happening, and we need to know now. But we need also need to be creative, and to do that we need to give ourselves time away from constant distractions, we need to give ourselves permission to think. We’d be better to think in terms of focus management rather than time management, if what we care about is the quality of our work, not how much of it we can cram into a day.